The Hunga Volcano: Past Eruptions and Geological History

International Tsunami Information Center, itic.tsunami@noaa.gov

M 5.8 Volcanic Eruption (USGS preliminary estimate 02-01-2021)

68 km NNW of Nuku‘alofa, Tonga, 20.546°S 175.390°W

2022-01-15 04:14:45 UTC (largest eruption, based seismic surface waves, USGS)

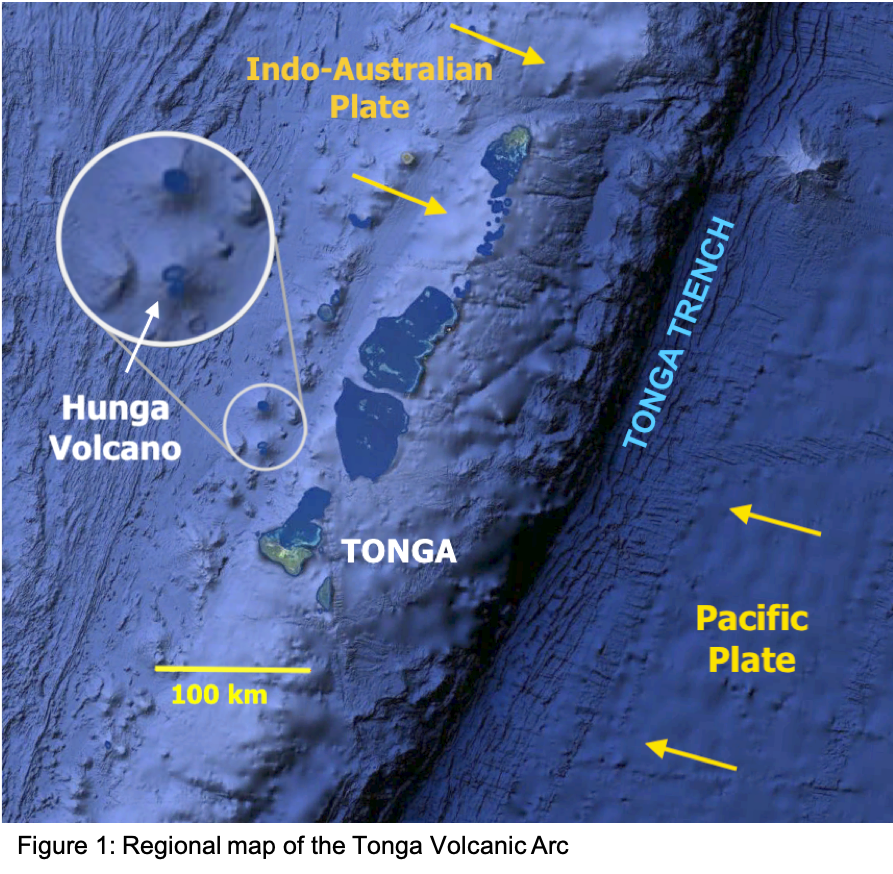

The volcanic islands of Tonga form a submarine ridge at the eastern edge of the Indo-Australian Plate where it is overriding the Pacific Plate (Figure 1), forming the Tonga Trench, the second deepest ocean trench in the world (10,800 meters). The island arc extends about 500 km, with seamounts and volcanoes rising up from a depth of over 2000 meters. Standing 1800 meters high and 20 kilometers wide, the submarine Hunga volcano is in the southern portion of the arc, about 65 km north of the inhabited island of Tongatapu where the Tongan capitol is located. The topography and paleomagnetic data of the volcanoes in the Tonga arc indicate their formation has been relatively recent, and small to moderate sized eruptions occur every few years; individual volcanoes erupt with periods of 20-50 years (Bryan et al. 1972).

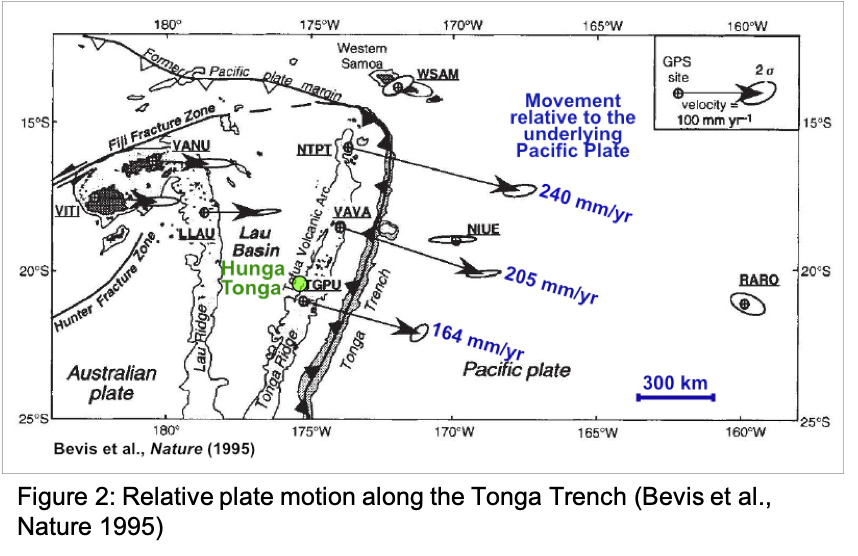

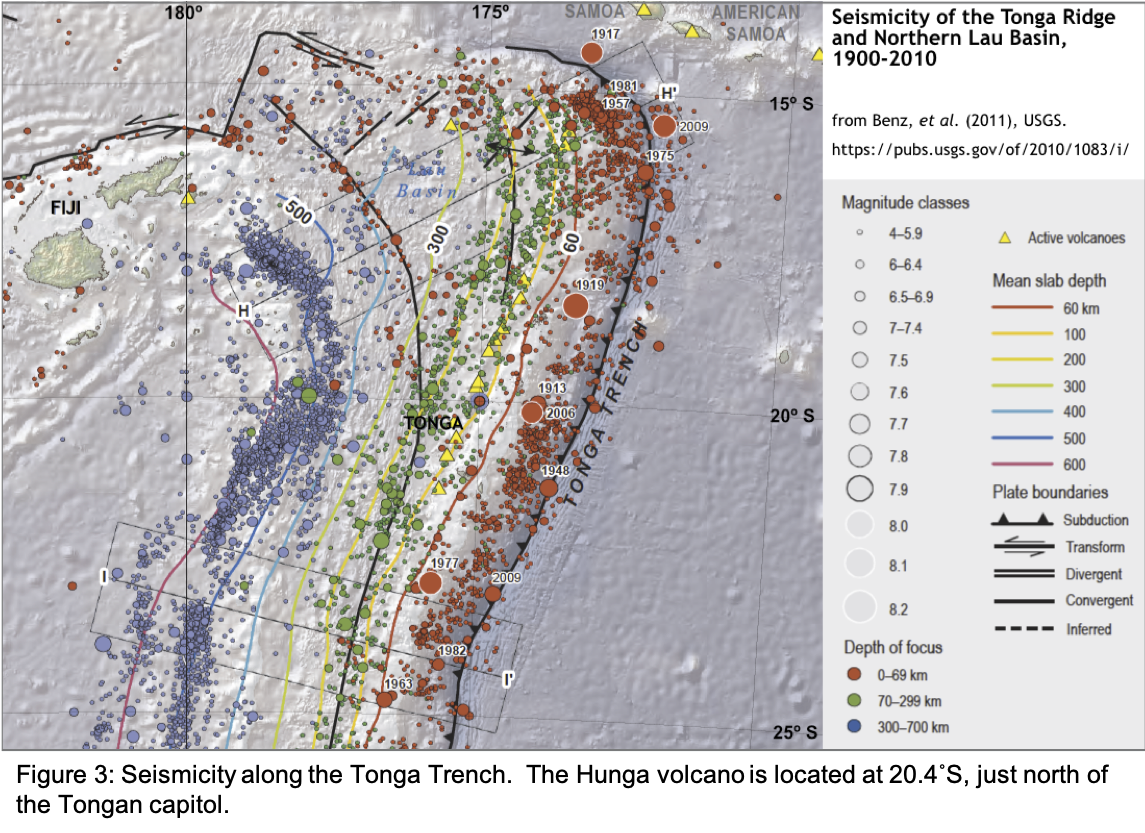

The island arc also lies at the eastern boundary of the rapidly spreading Lau Basin, and through the combination of convergence of the larger plates and divergence of the basin, the relative plate motion has been measured at 164 mm/yr on the southern end to 240 mm/yr at the north, the fastest subduction rate ever measured (Figure 2; Pelletier & Louat, 1989; Bevis et al., 1995; Smith and Price, 2006). The rapid subduction, as well as possible strain from the Pacific Plate bending around the Australian, gives rise to extreme seismic activity (Figure 3).

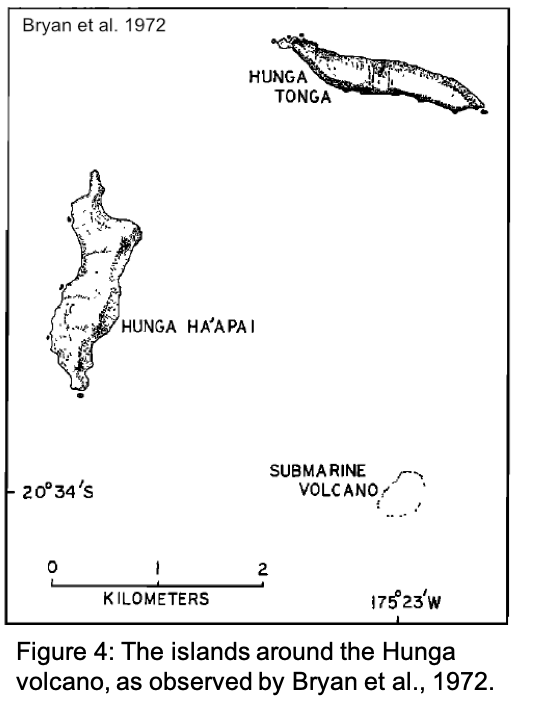

The site of the January 2022 eruption was near the uninhabited islands Hunga Tonga (to the north) and Hunga Ha’apai (on the west). The two islands are described by Bryan et al. (1972) as “elongated and tangent to a circle centered on a rocky shoal about 3 km to the south of Hunga Tonga, which was the site of volcanic eruptions in 1912 and 1937” (Figure 4). Samples collected on Hunga Tonga revealed “alternating layers of andesitic lava flows and beds of scoria [porous lava rock], lapilli [“little stones” of erupted lava], and ash, which dip gently away from the center of the circle.” They hypothesized that the islands were the visible northern and western remnants of the ridge around a large submarine caldera atop an active volcano.

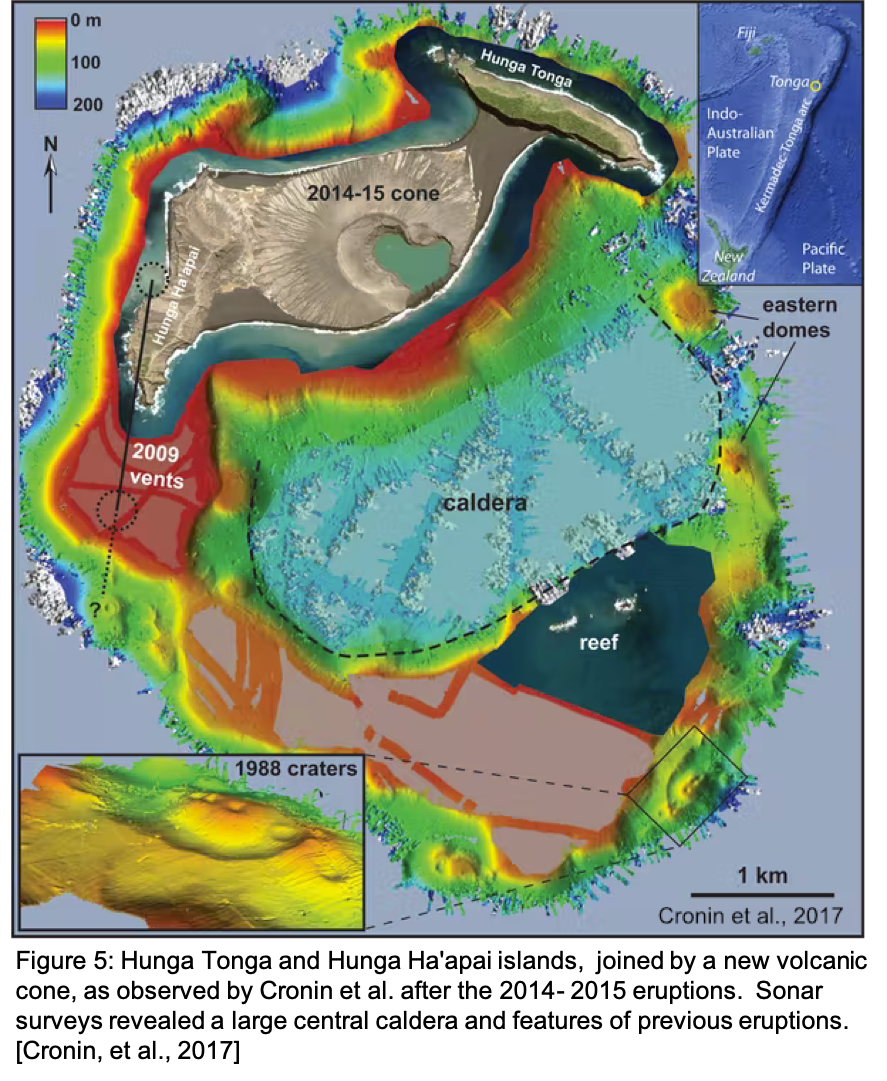

Further eruptions of the Hunga volcano were recorded in 1988 (3 days) and 2009 (1 week). On 19 December 2014 another eruptive event occurred that lasted for 5 weeks. Plumes of steam 17 kilometers high formed from the violent reaction of seawater with hot magma. The 2014-2015 eruptions created a cone that initially formed a third island; soon it merged with Hunga Ha’apai and eventually joined with Hunga Tonga to form a single island.

Shane Cronin and a team of researchers from the University of Aukland (NZ) and the Tonga Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources surveyed the new formation later in 2015 (Figure 5). The team also uncovered previous deposits from superheated pyroclastic flows, evidence of huge explosive eruptions over millennial time spans. One contained carbon dated to around 1100 CE, closely corresponding to an event in 1108 CE that resulted in global temperature cooling by 1°C (Cronin et al., 2017; Sigl et al., 2015). High-resolution multibeam sonar surveys also revealed a 4 × 2 kilometer, 150 meter deep depression in the location of the submarine caldera anticipated Bryan et al. (1972). A feature of this size would form by the explosive collapse of a previous volcanic structure in the course of an earlier eruption.

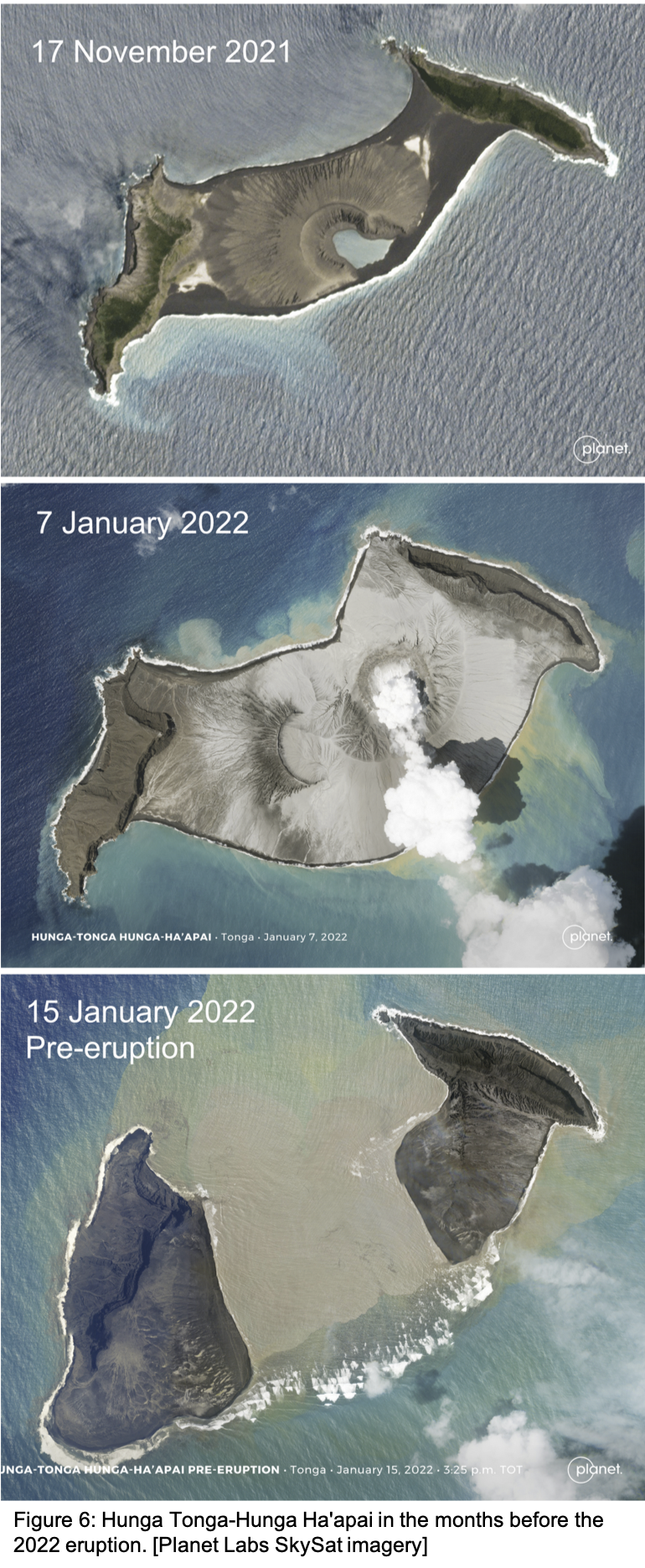

By November 2021, despite some shoreline erosion and settling, Hunga Tonga – Hunga Ha’apai appeared much the same as in late 2015 (Figure 6, top). Then on December 20th and January 13th two moderate eruptions occurred. The first increased the land area of the combined island (center), while the second added area to the western island but submerged the entire middle formed by the 2015 cone, splitting the formation in two once again (bottom).

Cronin notes that smaller eruptions typically occur around the edge of the central caldera, but large ones erupt from the caldera itself and introduce fresh, gas-charged magma with even more violent power. The massive explosion at 0415 GMT on January 15th appeared to confirm that. The explosive reaction of magma and seawater 150-200 meters below the surface can create plumes like those seen in 2015, but the eruption in 2022 sent a plume over twice as high, 39 kilometers into the atmosphere, with a diameter of 260 kilometers — from an explosion that lasted only about 10 minutes (Figure 7).

The tsunami that followed the Hunga eruption was different in several respects from the tsunamis following large earthquakes, which are much more common. First, unlike an earthquake that displaces ocean water from the seafloor up, along a fault line that can be hundreds of kilometers long, a volcanic explosion is more like a point source. Current tsunami forecasting models are based on the characteristics of 100 kilometer long segments of subduction zone faults in areas known to generate tsunamis. Volcanic eruptions do not fit this type of model, so estimates of travel time and wave height must be calculated differently, from observations of the tsunami waves themselves at the nearest tide stations or buoys.

In addition, more than one mechanism can produce a tsunami in a large volcanic eruption, and all differ substantially from subduction zone earthquakes:

Just weeks after the Hunga eruption, it is not known yet which of the first three mechanisms were responsible for the main tsunami (i.e., the tsunami generated directly in the ocean near the source). But strong atmospheric pressure waves were observed circling the globe several times, and tsunami-like waves reached remote regions such as the Caribbean too fast and at too great a height to have traveled through water the entire distance from Tonga, so the fourth mechanism must certainly have played a role.

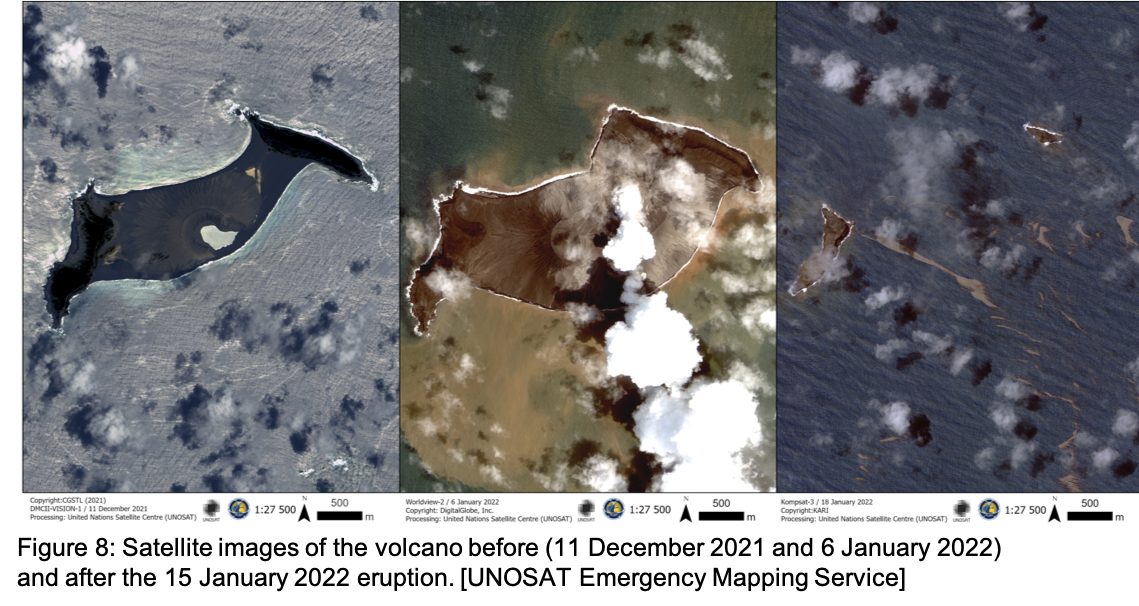

Post-eruption satellite images show what appear to be smaller remnants of the two rim islands, with scattered shoals of debris (Figure 8). Findings from the survey in 2015 suggest that massive eruptions like that in January 2022 occur only every 1000 years or so, but the period of activity each event covers varies. Material uncovered from previous events appears to have been deposited over the course of multiple explosions, so the eruptive forecast for the coming months and years is uncertain.

References and further reading:

(Detailed bathymetry and seismicity map of the area from New Zealand to Vanuatu.)

Bryan, W., G. Stice and A. Ewart (1972) Geology, Petrography, and Geochemistry of the Volcanic Islands of Tonga. J. Geophysical Research 77 (8): 1566-1585.

https://doi.org/10.1029/JB077i008p01566

NOAA

NOAA