Seismic Signals, Early Warning Systems and Event Documentation

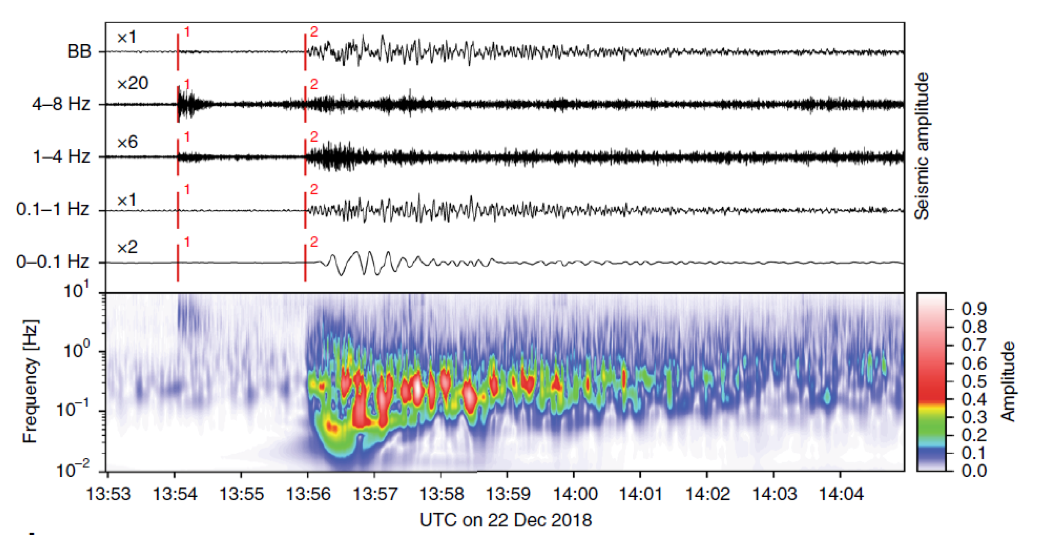

The local monitoring network was almost totally destroyed during the event (see Kristianto et al.), and remote seismic monitors did not detect signals typical of the body waves produced by earthquakes. However, a precursor to the collapse is seen in remote seismic and infrasound records 115 seconds prior to the event (Walter et al., 2019). The subaerial landslide itself is marked by low frequency (0-1 Hz) signals lasting about 2 minutes. A period of intense energy at higher frequencies follows for about 5 minutes and further seismic and infrasound activity associated with continuing large eruptions lasts for several hours. These seismic signals were not identifiable in the very active eruption period before the collapse but were detectable even remotely afterwards. The frequency of the infrasound signals changed dramatically during this period, and suggests “a profound change in eruptive style following the landslide,” likely linked to changes in the internal structure of the collapsing edifice such as that suggested by Williams et al., and the transition to violent underwater Sturseyan action seen clearly the next day and for an extended period after.

A seismic station 64 km from Anak Krakatau revealing the occurrence of a high-frequency

A seismic station 64 km from Anak Krakatau revealing the occurrence of a high-frequency

event (1) 115 s prior to the sector collapse (2). The spectrogram reveals that collapse

is a 1–2-minute-long low-frequency signal presumably related to the landslide,

followed by ~5 mins of strong emissions at high frequencies (Walter et al., 2019).

Volcanic sector collapses large enough to cause tsunamis are common throughout geological history. However, they are infrequent on human time scales. As a result, concrete data that can be used to understand the progression of events and develop early warning systems is scarce.

Monitoring and analysis of multiple parameters, both locally and remotely, from gradual flank motions to infrasound, is recommended to further understand and warn vulnerable populations about changes occurring within island volcanoes that could lead to catastrophic destabilization.

A number of monitoring and recording methods have also been helpful in post-eruption analysis and modeling. Video footage of landslides was very useful to develop time varying tsunami sources. The simulated solutions for tsunami run-up compared well with field survey data at several locations. Surveying techniques such as air reconnaissance, drones and videography were found to be efficient in deducing flow velocity and estimating the extent of damage.

Contents

- History

- Post-tsunami Eruptions and Cone Regrowth

- 22 December 2018 Eruptions and Tsunami

- Tsunami Impact on Nearby Unpopulated Islands

- Tsunami Impact on Populated Coastlines of Sumatra and Java

- Tsunamagenic Flank Failure Scenarios

- Seismic Signals, Early Warning Wystems and Event Documentation

- Lessons Learned

- Event Information

- Krakatau Islands History

- Media Reports, Photos and Video

- Research Articles

NOAA

NOAA