The Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Disaster - Part 2: Decades of environmental consequences

For Part 1: Uncharted territory for a nuclear emergency click here

The immediate priority after the March 11 tsunami inundation was restoring power to the site and restoring cooling systems to the reactors and spent fuel facilities to prevent exposure of the fuel rods and buildup of pressure from heat released by continued radioactive decay. Improvised measures such as spraying the spent fuel pools with fire hoses and water cannons continued through the month. After power was restored to reactors at the site in late March 2011, conditions remained precarious. It was late July before reactors 1-3 met the first criteria for concluding the “accident” phase of the response: achievement of significant suppression of radiological releases and steady decline of radiation dose rates. Safety systems were not stabilized until March-April of 2012.

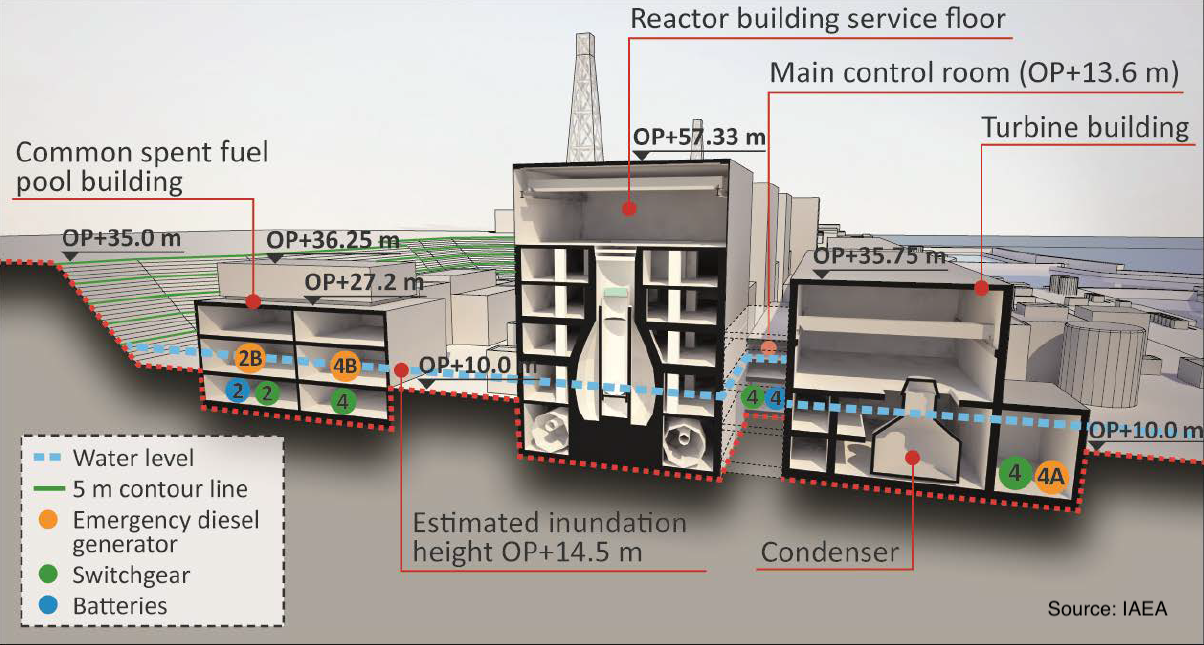

Cutaway of the major buildings on the Fukushima site and

Cutaway of the major buildings on the Fukushima site and

the water level after the tsunami. (International Atomic Energy Agency)

Public health concerns

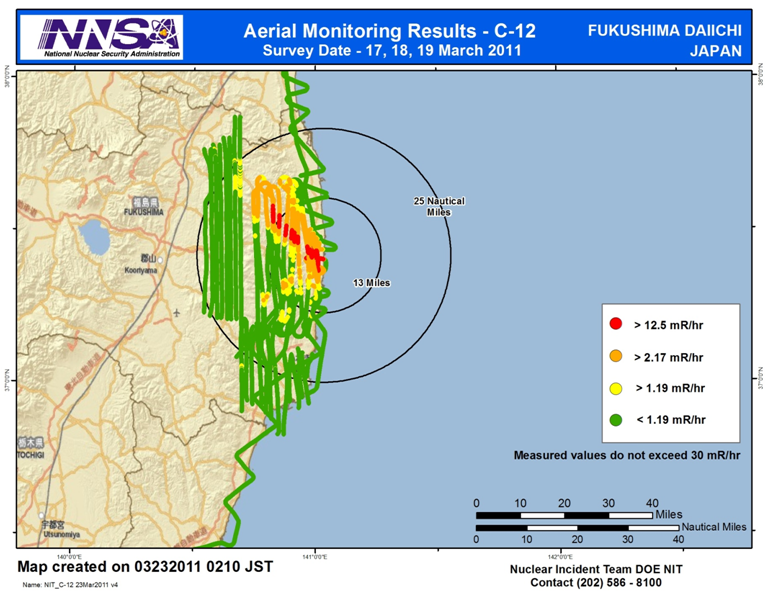

A week after the beginning of the accident U.S. military aircraft collected radiation data over a radius of 45 kilometers. The data showed a radiation level more than 125 μSv per hour spread over a 25 km (15 mile) radius as well as in a longer plume to the northwest of the plant, a location that was being used for evacuations. At that rate of exposure any residents would reach the standard permissible level for the public (1000 μSv/yr above background) within eight hours.

Aerial monitoring results from the 17-19 March 2011 survey show that more than 125 μSv of radiation per hour were detected as far as 25 km (13 nm) northwest of the Fukushima Daiichi.

Aerial monitoring results from the 17-19 March 2011 survey show that more than 125 μSv of radiation per hour were detected as far as 25 km (13 nm) northwest of the Fukushima Daiichi.

(mR = millirem; 10 mR = 100 μSv)

A series of evacuation orders were issued by the government during the first month of the disaster. The first, for residents within 2 km of the plant, was issued at 20:50 on March 11, 5 hours after the second wave inundated the site. Within an hour it was expanded to 3 km. When radiation and pressure containment deteriorated further the next day, the zone was expanded to 10 km, then 20 km. A month after the accident an “evacuation prepared area” was established 20-30 km from the site in case of further emergencies.

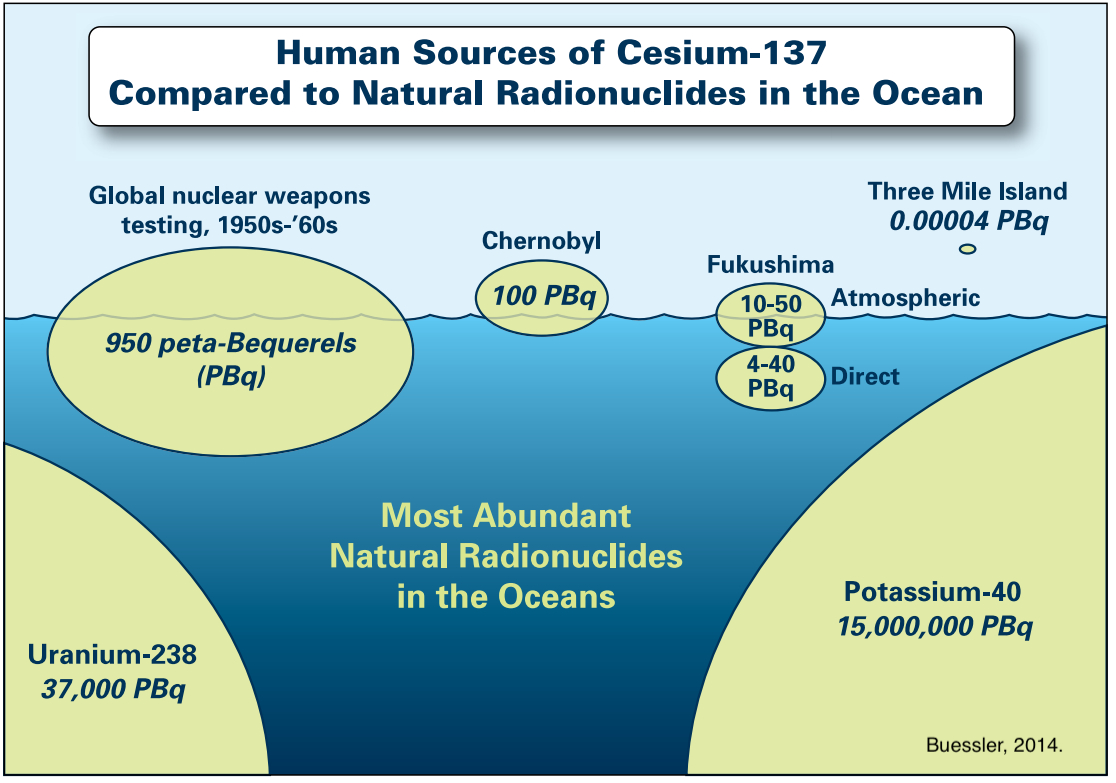

In the ocean off Japan, concentrations of radioactive cesium (Cs-137) from the power plant were found to be up to 1000 times higher than normal background levels over a 150,000 square kilometer area in the months after the accident. However, normal levels are extremely low and dilution and mixing in the ocean is very high. Even at the elevated concentrations measured in 2011 the radioactivity was just a small fraction of that produced by other naturally occurring radioactive elements in seawater such as Potassium-40. The activity of cesium measured in marine organisms was likewise well below that from naturally occurring Potassium-40.

Natural and anthropogenic sources of radiation in the ocean. (Buessler, 2014)

Natural and anthropogenic sources of radiation in the ocean. (Buessler, 2014)

In 2013-2017 scientists also discovered unexpected reservoirs of radiation comparable to those at the source. Cesium had adhered to sand particles in semi-fresh groundwater and was being released as it was gradually flushed with seawater. Contrary to expectations, the highest levels of cesium were found not in the plant itself or the harbor, but in nearshore groundwater 10 km from the site where it was up to 10 times the level in the harbor. Fortunately brackish groundwater near the ocean is not used for human consumption so it does not pose an immediate health risk, but the findings underscore the need to fully understand environmental pathways of contaminants.

Containment and clean-up

Release to the air was reduced significantly by August 2011 and to near zero by February 2012. Containing and preventing leaks into the ocean and soil have been much more problematic because of tsunami damage to foundations and structures, damage from explosions, and the enormous (and still growing) volume of contaminated cooling water.

After ten years, over 1.24 million gallons of contaminated water had accumulated. Because intact, spent and melted fuel continue to decay and release heat, the water will continue to accumulate until all the fuel has been removed from the reactors and reservoirs. More than 1000 tanks of contaminated water are currently crowding the site, and space is expected to run out some time this year (2022). The used cooling water is contaminated with tritium, which releases low levels of radiation, but also trace amounts of other more hazardous radioactive isotopes which need to be removed before release to the environment. Construction of the final containment structure for reactor 1 is still to be completed as engineers work out how to remove fuel from the highly damaged core. TEPCO estimates it will take at least 30 more years of work to clean up unused and melted fuel, remove contaminated cooling water and decommission the plant.

Storage tanks for contaminated cooling water at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear site.

Storage tanks for contaminated cooling water at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear site.

More than 160,000 people were evacuated from the 20+ km zone around the plant and 37,000 residents are still cut off from their homes and community because of hazardous environmental conditions. In a portion of Futuba, Fukushima Prefecture, decontamination of one of the hardest hit areas is expected to be complete this summer (2022). This week, eleven years after the tsunami and nuclear disaster, some residents are being allowed to visit and spend the night in their homes for the first time.

References & Further Information

Why cleaning up Fukushima's damaged reactors will take another 30 years

https://www.science.org/content/article/why-cleaning-fukushima-s-damaged-reactors-will-take-another-30-years

Fukushima-derived radionuclides in the ocean and biota off Japan.

Buessler, et al. (2012) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3341070/

Evaluation of radiation doses and associated risk from the Fukushima nuclear accident to marine biota and human consumers of seafood. Fisher et al. (2013) https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1221834110

Fukushima and ocean radioactivity.

Buessler (2014) http://dx.doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2014.02

Scientists Find New Source of Radioactivity from Fukushima Disaster

https://www.whoi.edu/press-room/news-release/scientists-find-new-source-of-radioactivity-fromfukushima- disaster/

Mainichi Daily: Crisis-hit Fukushima town finally allows residents to stay overnight

https://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20220120/p2g/00m/0na/033000c

FAQs: Radiation from Fukushima, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

https://www.whoi.edu/know-your-ocean/ocean-topics/pollution/fukushima-radiation/faqs-radiationfrom- fukushima/

NOAA

NOAA