Tsunamagenic Flank Failure Scenarios

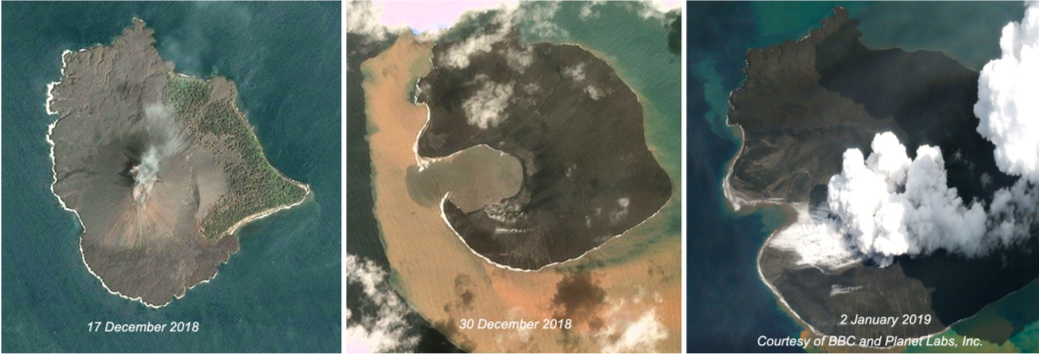

Left: Planet Lab's Dove satellite captured this clear image of the 338-m-high cone with a summit crater on 17 December 2018. Center: The skies cleared enough on 30 December to reveal the new crater in place of the former cone after the explosions and tsunami of 22-23 December, and multiple subsequent explosions. Right: Surtseyan explosions continued daily through 6 January. Courtesy of BBC and Planet Labs, Inc.

Left: Planet Lab's Dove satellite captured this clear image of the 338-m-high cone with a summit crater on 17 December 2018. Center: The skies cleared enough on 30 December to reveal the new crater in place of the former cone after the explosions and tsunami of 22-23 December, and multiple subsequent explosions. Right: Surtseyan explosions continued daily through 6 January. Courtesy of BBC and Planet Labs, Inc.

Much research has been focused on determining the mechanism of the flank collapse, including the timing and volume. Although 2 cubic km of material was ultimately removed by the eruptions of 22-23 December, consensus is that the landslide responsible for the tsunami was only the initial failure with a fraction of that volume. Understanding the potential for even small volcanic landslides to produce damaging tsunamis is critical for providing timely warnings when seismic signals are not present.

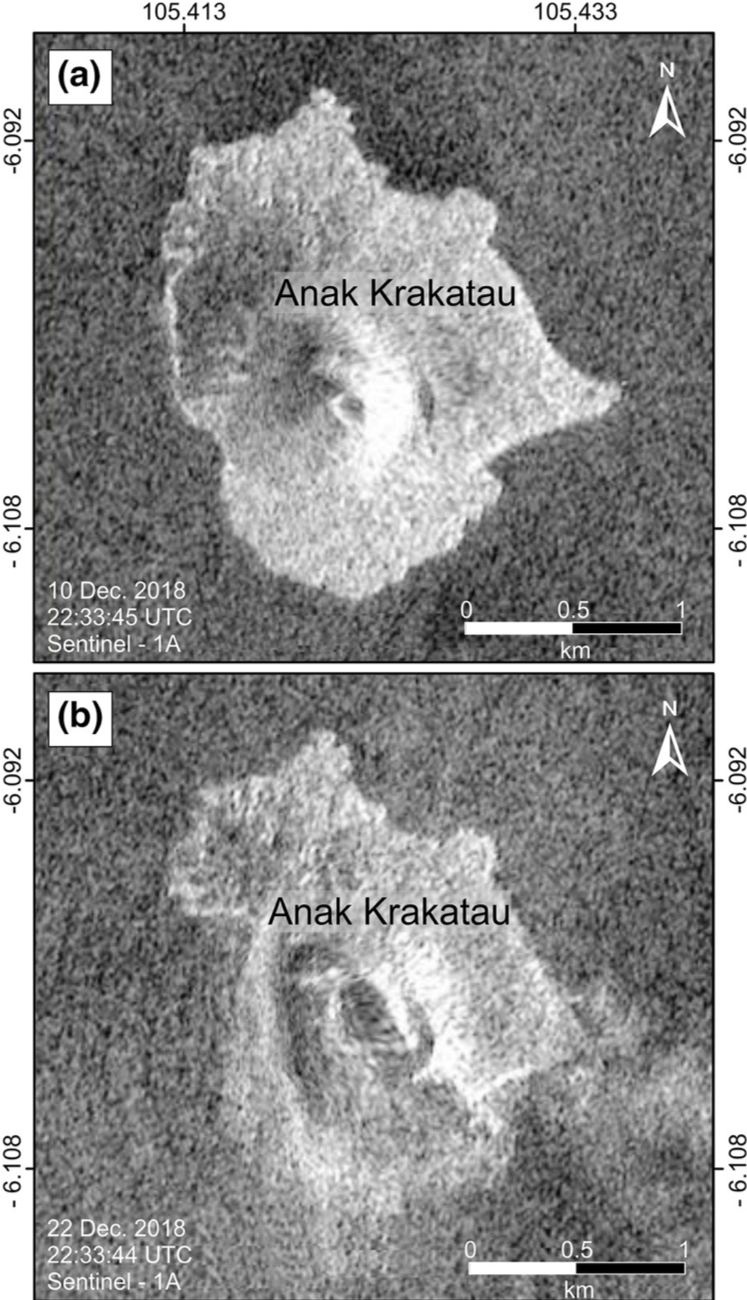

Synthetic aperture radar (SAR) image from Sentinel 1-A.

Top: 12 days before collapse. Bottom: 8 hours after tsunami.

Differing explanations of the volume and timing of the collapse have been offered, based on available observations (satellite images; seismic and acoustic data; tsunami height and speed; eyewitness accounts) as well as modeling studies stemming from the observations. Numerous satellite images were captured before and after the collapse, including the Sentinal 1-A synthetic aperture radar (SAR) image from approximately 8 hrs post-tsunami. However clear visible images and aerial photographs showing the timing and extent of the collapse are lacking until days afterward because of the time of day and plume debris. Likewise little is known about the volume or geometry of the flank collapse below sea level. Major considerations that continue to be explored include:

- Interpretation of features in the 8-hr post-tsunami Sentinal 1-A SAR image, particularly the location of the collapse margin at that time (in front of the cone or consuming it)

- Total volume of the landslide causing the tsunami. Estimates used to model the collapse range from 0.104 cu km (Williams et al.) to 0.27 cu km (Grilli et al.)

- Volume of the subaerial landslide material. Many studies argue that the bulk of the landslide was submarine, not subaerial (e.g., Ye et al., Williams et al.) but subaerial estimates range from as low as 0.004 cu km (Williams et al.) to nearly half the total volume, ~0.15 cu km (Grilli et al.).

- Timing of the flank failure: a single massive collapse (e.g., Grilli et al., Perttu et al. ), piecemeal in a rapid series of collapses (e.g., Omira & Ramalho), or over a period of days (Williams et al., Ye et al.)

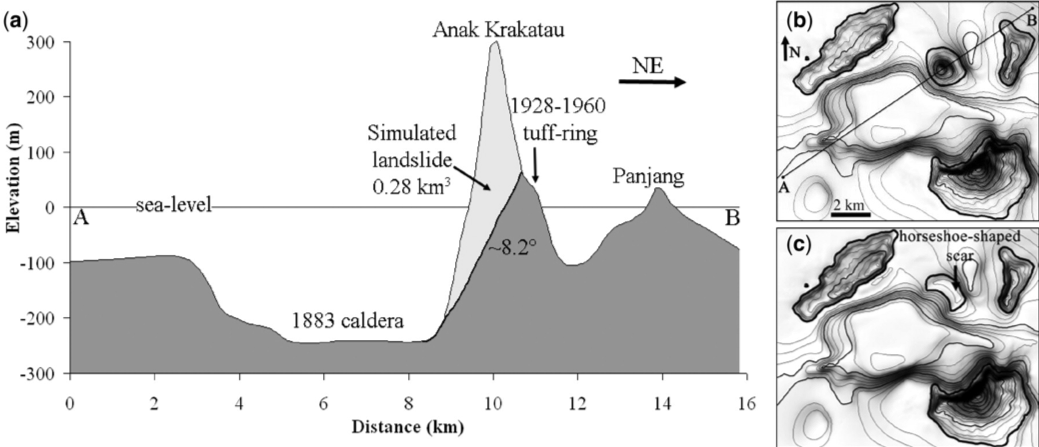

The scenario predicted by Giachetti et al. In 2012. (a) Cross-section of Anak Krakatau and the 1883 eruption caldera. The landslide scar, defined by modifying some level lines on our initial DEM, is drawn in black. It is orientated southwestwards, with a slope of 8.2°, delimiting a collapsing volume of about 0.28 km3. (b) Topography before the simulated landslide, with the location of the cross-section presented in (a). The caldera resulting from the 1883 Krakatau eruption is clearly visible, as well as Anak Krakatau, which is built on the NE flank of this caldera. (c) Topography after the simulated landslide, with the horseshoe-shaped scar clearly visible.

The scenario predicted by Giachetti et al. In 2012. (a) Cross-section of Anak Krakatau and the 1883 eruption caldera. The landslide scar, defined by modifying some level lines on our initial DEM, is drawn in black. It is orientated southwestwards, with a slope of 8.2°, delimiting a collapsing volume of about 0.28 km3. (b) Topography before the simulated landslide, with the location of the cross-section presented in (a). The caldera resulting from the 1883 Krakatau eruption is clearly visible, as well as Anak Krakatau, which is built on the NE flank of this caldera. (c) Topography after the simulated landslide, with the horseshoe-shaped scar clearly visible.

Contents

- History

- Post-tsunami Eruptions and Cone Regrowth

- 22 December 2018 Eruptions and Tsunami

- Tsunami Impact on Nearby Unpopulated Islands

- Tsunami Impact on Populated Coastlines of Sumatra and Java

- Tsunamagenic Flank Failure Scenarios

- Seismic Signals, Early Warning Wystems and Event Documentation

- Lessons Learned

- Event Information

- Krakatau Islands History

- Media Reports, Photos and Video

- Research Articles

NOAA

NOAA