The Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Disaster - Part 1: Uncharted territory for a nuclear emergency

For Part 2: Decades of environmental consequences, click here

11 March 2011, 05:46:24 UTC, 14:46:34 JST

Mw 9.1 Earthquake, 38.297°N, 142.372°E, depth 20 km

Maximum tsunami runup 39.7 m

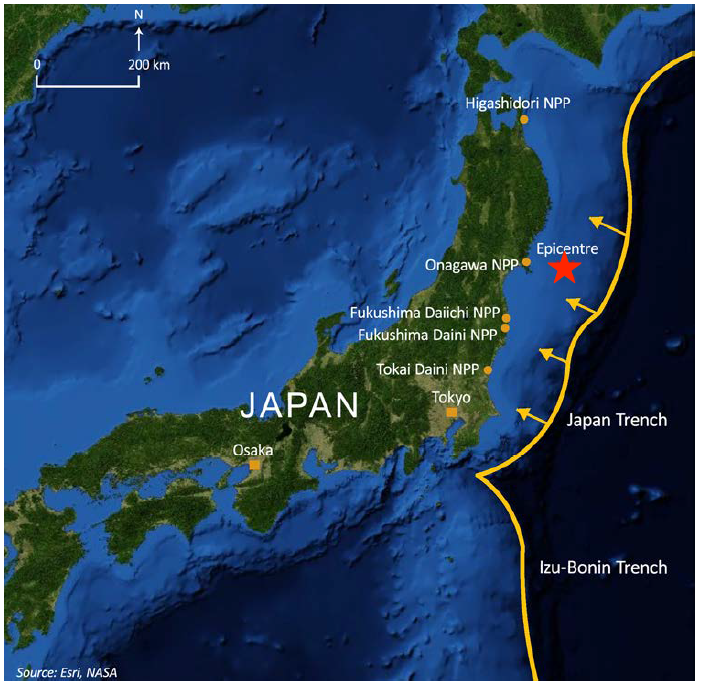

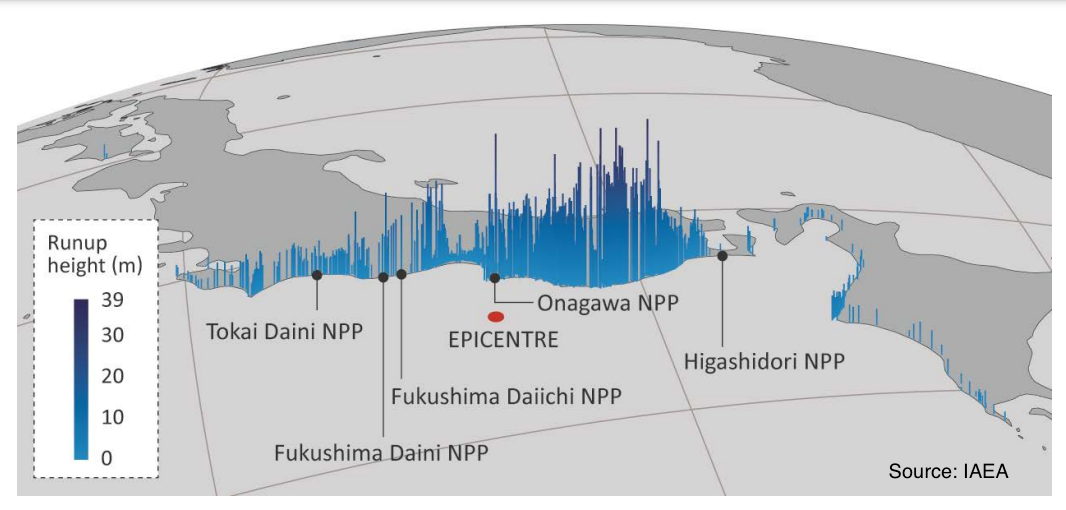

Seismic setting of the 2011 Great Japan Earthquake and nuclear power plants. (NPP)

Seismic setting of the 2011 Great Japan Earthquake and nuclear power plants. (NPP)

On 11 March 2011 at 14:46 local time a Mw 9.1 earthquake near the Japan Trench triggered a massive tsunami that within 30 minutes struck the coast of Honshu, the main island of Japan. Protective seawalls were overrun and towns on the northeast coast of the island sustained catastrophic damage. In the Sendai region, due west of the epicenter, the tsunami bore reached 5 km inland to a depth of 19.5 m. Embayments on the coastline to the north saw water heights up to twice that. A t Miyako, 145 km (90 mi) NNW of the epicenter, the water reached a height of 39.7 m. Of the approximately 18,000 people who died, more than 90% were drowned. The Geospatial Information Authority of Japan estimated that 561 square kilometers were area inundated by the tsunami. Approximately 500,000 people lost their houses and were displaced.

Five nuclear power plants along the northeast coast of Honshu were also affected. Approximately 175 km (110 mi) southwest of the epicenter, the Fukushima Daiichi power plant experienced a combination of damage from the earthquake and subsequent tsunami that set off a chain of events leading to the meltdown of three reactor cores and release of radiation into the atmosphere and ocean. While the earthquake damaged the external power supplies, the situation was within the capacity of normal emergency procedures. The damage inflicted by the tsunami was not.

Locations of the 5 nuclear power plants (NPP) on the northeast coast of Honshu, Japan,

Locations of the 5 nuclear power plants (NPP) on the northeast coast of Honshu, Japan,

and tsunami run-up heights. (International Atomic Energy Agency)

The Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant

The Fukushima Daiichi facility, owned by the Tokyo Electric Power Co. (TEPCO), contained 6 reactors, of which 3 were fully online at the time of the earthquake, generating 460-784 Mw of electricity each. The reactor complex was guarded by a protective seawall designed for a maximum wave height of 5.5 m. Plant facilities were powered by offsite electricity. In case of emergency, 13 diesel generators provided backup power to the reactors and equipment requiring DC battery chargers.

Buildings housing reactors 1-4 and facilities for waste and spent fuel were in an area 10 m above sea level. Buildings for reactors 5-6 and the emergency generators were in an area 13 m above sea level. The lowest floors of the buildings were one level below ground, near sea level. The main administration building was up slope behind the reactor complex at an elevation of 35 m. Seawater providing cooling for the reactor cores and generators was pumped in through six intakes at the shoreline. Spent fuel pools also relied on seawater cooling to dissipate heat from continued radioactive decay.

Tsunami risk had been assessed by TEPCO staff as recently as 2008, when an employee submitted a tsunami height estimate of 15.7 meters based on extensive seismic studies and the 1896 Sanriku earthquake that triggered a tsunami over 30 m high. The employee testified that the company requested an alternate calculation, which returned nearly identical results, and ultimately rejected the estimate in favor of commissioning an additional engineering study.

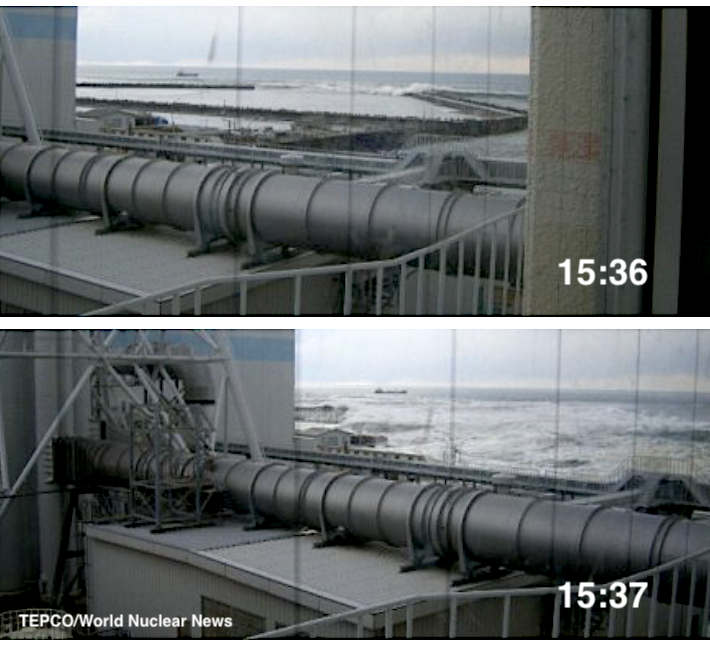

Photographs taken by a Fukushima Daiichi employee

Photographs taken by a Fukushima Daiichi employee

as the second and largest wave breached the 5.7 meter sea wall.

Earthquake and first tsunami arrivals

When the earthquake struck, seismic sensors at the plant activated automatic insertion of control rods in the reactor cores to immediately stop the nuclear reactions. However the violence of the ground movement damaged electrical substations and power lines, resulting in the loss of offsite power to the plant. After shaking subsided, emergency operations proceeded according to the facility design, including automatic reactor shutdowns, conversion to diesel generator power, setup of an emergency response center, initiation of backup reactor cooling systems, and monitoring of spent fuel pool temperature.

The Japan Meteorological Agency issued a tsunami warning for 3-4 m waves within minutes after the earthquake, soon after updating it to 6 m. The first wave (4 m) arrived in 41 minutes (A third warning update was issued a few minutes later for waves up to 10 m and all lower elevation facilities were evacuated. Ten minutes after the first, a 14-15 m wave arrived, surrounding the entire reactor complex.

Photographs at 1-min intervals of tsunami flooding.

Photographs at 1-min intervals of tsunami flooding.North side of Radiation Waste Treatment Facility,taken from 4th floor.

Source: https://photo.tepco.co.jp/en/date/2011/201105-e/110519-02e.html

Flooding damage to the seawater intake pumps rendered all of them inoperable. Equipment, machinery and electrical systems in the reactor complex buildings were damaged by water filling the ground floors and any levels below. All but one of the 13 diesel generators were damaged, resulting in the loss of AC power to all facilities except reactor 6. Backup battery systems in reactors 1, 2 and 4 were also flooded, shutting down instruments that enabled monitoring of temperature, pressure and water levels in the reactors and spent fuel pools. As a result, operators were unable to determine critical safety conditions in reactors 1 and 2 whose cores were active at the onset of the earthquake.

At 16:45, two hours after the earthquake, the plant reported nuclear emergency conditions for reactors 1 and 2 based on inability to confirm their cooling status. Soon after there was confirmation that the cooling system in reactor 1 was not working.

Deteriorating conditions

At 19:03 on March 11, a national nuclear emergency was declared by the Japanese government. With no cooling system, water that evaporates from the hot core cannot be replenished. Eventually water levels drop enough to expose the fuel rods, leading to uncontrolled heating and melting of the rods. The melted material is hot enough that it can penetrate the base of the containment structure and descend into the ground below.

Evacuation orders for the area were issued when technicians estimated the fuel rods would become exposed in 40 minutes. Half an hour later increasing radiation levels around reactor 1 confirmed the core was exposed. Just before midnight on March 11 the first pressure readings inside the reactor were possible and readings were higher than the maximum containment design pressure. Overnight a slight pressure drop was accompanied by a tenfold increase in radiation outside the vessel.

Crews worked to establish alternate cooling systems for the reactors using the plant’s diesel fire pump, fire trucks, and onsite firefighting freshwater tanks. Complications arose because of difficulty establishing connections through debris from the tsunami, frequent strong aftershocks, and fluctuating radiation levels across the site that required crews to cease work and evacuate. Twenty three hours into the emergency at 15:36 on March 12, just as work was concluding for an emergency AC power cable and seawater delivered by fire hose, they were destroyed by an explosion in reactor 1, probably from a buildup of hydrogen gas.

Fukushima power station after Japan’s 2011 triple disaster, reactors 3 and 4. (Ho New/Reuters)

Fukushima power station after Japan’s 2011 triple disaster, reactors 3 and 4. (Ho New/Reuters)

Over the following days numerous other explosions occurred. On March 13 an explosion destroyed the entire upper level of reactor 3, damaging the venting system on reactor 2, and forcing an evacuation which delayed the restoration of cooling to reactor 1. Reactors 2 and 4 exploded on March 15 and hundreds of employees were evacuated. After a release of white smoke, radiation at the main gate to the plant reached 12 mSv per hour. At that rate the annual limit for uranium miners and nuclear industry workers (20 mSv/yr) would be exceeded in less than 2 hours. When crews attempted to enter reactor 4 their dosimeters maxed out at the instruments’ highest reading, 1000 mSv/hr.

Ultimately all power to reactors 1 and 2 was lost for 9 days, and to reactor 3 for 14 days. Explosions and evacuations left reactors entirely without cooling for hours at a time. At one point reactor 1 had no cooling for 18 hours. All three reactor cores were exposed, fuel rods melted through the inner pressure vessels, and radiation breached damaged containment vessels or was released by preemptive venting. Radiation released from the plant was deposited on land and in the ocean by atmospheric fallout, and leaked directly into the soil, sediments, and coastal waters.

References & Further Information

NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information Event Page

https://www.ngdc.noaa.gov/hazel/view/hazards/tsunami/event-more-info/5413

The Fukushima Daiichi Accident, Technical Volume 1: Description and context of the accident. 2015.

International Atomic Energy Ageny, Vienna, Austria. 236 pp.

https://www.iaea.org/publications/10962/the-fukushima-daiichi-accident

Survey of 2011 Tohoku earthquake tsunami inundation and run-up.

Mori et al. (2011) https://doi.org/10.1029/2011GL049210

Mainichi Daily: Plant tsunami preparedness investigations

https://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20180301/p2a/00m/0na/003000c

What Happens During a Nuclear Meltdown?

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/nuclear-energy-primer

NOAA

NOAA